Building a Programming Language

Before building a compiler, we need to define the language it will compile. A programming language isn’t just syntax and semantics—it’s the user interface between humans and computers.

What Is a Programming Language?

Abstraction is one of the core ideas in computer science. Without abstraction, interacting with computers would require understanding electrical signals, memory layout, registers, and countless hardware details.

A programming language simplifies this complexity. It provides a human-friendly way to express ideas while hiding the low-level mechanisms that make them work. In this sense, a programming language functions as a UI for computing—a layer that lets us focus on building logic, applications, and systems, rather than manually manipulating hardware.

Whatever language you choose—Python, Rust, C++, Go, or something entirely new—its purpose is the same: turn human intention into machine behavior. First, let’s see what options we’ve got for designin our own programming language.

Compiled vs. Interpreted

Programming language implementations are often categorized by how they execute code:

- Compiled languages

- Interpreted languages

A compiled language translates the entire source code into machine instructions before execution. Once compiled, the program can run directly on the hardware, resulting in high performance and efficient CPU usage.

An interpreted language, on the other hand, executes code step-by-step. The interpreter reads each instruction and performs it immediately, without producing a standalone machine binary.

A simple analogy:

Imagine you have a recipe book written in French.

- With an interpreter, you translate each sentence as you read it and cook immediately.

- With a compiler, you translate the entire cookbook into your language first and then cook smoothly without stopping.

Compiled languages (like C, C++, or Rust) typically offer speed, safety analyses, and optimization, but require recompilation when the code changes. Interpreted languages (like Python, Ruby, or Perl) prioritize convenience, interactivity, and flexibility—especially during early development—but generally run slower. This is why C is generally faster than Python. C can have REPL-like environments, but they are uncommon and not part of the language’s standard toolchain.

Languages can be compiled & interpreted at same time

Actually, being “compiled language” or “interpreted language” is not property of language itself, but it is more accurate to view this distinction as a property of the language implementation rather than the language itself.

Languages based on JVM (Java Virtual Machine) can be both “compiled” and “interpreted”. Meaning, they can be compiled into machine code on the fly at runtime using a Just-In-Time compiler, or they can be interpreted. Typically, Java (or any other JVM based language) programs are first compiled to something called “bytecode”. Which is instruction for JVM, but not hardware-specific. This bytecode can be deployed anywhere that runs JVM, and it is JVM’s choice to compile them down to target-specific code, or interpret bytecode.

Moreover, Python is often described as an interpreted language, but in practice, its source code is first compiled into Python bytecode (.pyc files), which is then executed by the Python virtual machine. Some implementation like PyPy can compile Python down to machine code, just like JVMs do.

Managed vs. Unmanaged

Another useful distinction between languages is how they manage memory.

Programs need memory to run. They request memory from the operating system and should return it when finished. If they fail to do so, we get issues such as:

- Segmentation faults when accessing memory the program doesn’t own.

- Memory leaks when unused memory is never returned.

Managed languages automate memory handling, often using garbage collection or runtime analysis. This reduces the chance of memory-related mistakes and simplifies development. They typically use program called “Garbage Collector (GC)”, which automatically detects unreachable memory regions and frees them, so operating system can allocate that memory for another program (process). Some garbage collectors may stop the entire program (stop-the-world) during certain phases, although modern collectors often reduce or avoid long pauses using concurrent or incremental techniques. Garbage collectors are convenient, but might make programs run slower.

Example of managed programming language (Python)

# my_list is internally allocated

size = input()

# Python internally allocates memory space for storing list.

my_list = [x for x in range(0, int(size))]

# Do some work using my_list

# my_list is automatically deallocated after use

Unmanaged languages, like C/C++ give developers direct control. They provide APIs such as malloc and free, which ultimately request memory from the operating system through lower-level system calls. Programmers are responsible for making sure memory is allocated and freed correctly. Since unmanaged languages do not rely on garbage collectors, they avoid GC-related pauses such as stop-the-world events, but this shifts the responsibility of correctness and safety to the programmer or the compiler. Also, they give more optimization headroom since programmers can hand-optimize when to allocate and free memory. But managing this makes programs more complicated, and easier to break. (Rust uses a static ownership and borrowing system enforced by the compiler to achieve memory safety without garbage collection.)

Example of unmanaged programming language (C)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(){

int size;

scanf("%d", &size);

// Explicitly allocate aray

int* my_list = malloc(size * sizeof(int));

for(int i = 0; i < size; ++i){

my_list[i] = i;

}

// Do some work with my_list

// my_list has to be explicitly freed, or memory would leak.

free(my_list);

return 0;

}

Functional Programming

Finally, I’d like to briefly introduce functional programming, another paradigm of programming languages. While less commonly used than imperative languages, it’s a programming paradigm with significant advantages, which is why I want to introduce it. Functional programming allows you to write programs that produce significantly fewer bugs. Even if you’re not actively doing functional programming, knowing about it as a programmer helps you build more stable programs.

Functional programming languages are languages that compose programs out of mathematical functions, emphasizing function purity, value immutability, and how functions are composed. Functional languages express computation as the evaluation of expressions. The functions we define in mathematics can never produce different results when given the same input, right? Functional programming follows this way of thinking.

Here are simple examples of adding all numbers in a list.

Example of adding all values in a list in Python

my_list = [1,2,3,4,5]

sum = 0

for elem in my_list:

sum += elem

print(f"Sum : {sum}") # Prints "Sum : 15"

Example of functional language (F#)

let my_list = [1;2;3;4;5]

let sum = List.fold (fun acc elem -> acc + elem) 0 my_list

printfn "Sum : %A" sum // Prints "Sum : 15"

They both do the same thing, but the way they are written is a bit different, right?

Pure functional languages have constraints that other languages don’t have.

- All values (let bindings) are immutable

- No for loops (all iteration is done by recursion)

- However, the compiler can transform recursion to loops for optimization if the function is “tail-recursive” (we’ll explain more about this later)

- Multi-paradigm languages that support functional programming but aren’t purely functional may also provide for loops.

- Functions are “Pure”

- By “Pure”, we mean that functions don’t perform operations with side effects that the programmer isn’t aware of.

- Side effects refer to internal operations that aren’t explicitly visible, such as file I/O.

- Since there are no side effects, it’s safe to remove the function if its result is not used (Compilers can do aggressive dead code elimination)

- Functions always give the same result when given the same input

- By “Pure”, we mean that functions don’t perform operations with side effects that the programmer isn’t aware of.

Functional programming languages generally have a steeper learning curve, and many programmers aren’t familiar with functional languages. However, they come with some clear advantages.

Advantages of Functional Programming

- Since there are no side effects, programs are safer and easier to analyze for stability.

- Makes it easier for compilers to detect potential errors.

- Programs can be expressed more clearly. It focuses on “what to compute” rather than execution itself. (This might be a bit hard to grasp at first, but as you see implementations in functional languages, you’ll understand it more easily)

- Purity (pure functions) and immutability (value immutability) make it easier to write safe concurrent programs.

Explaining all the reasons listed above is beyond the scope of this chapter, but as we continue building our programming language, you’ll understand why these problems are important and what advantages functional languages have compared to regular programming languages.

Of course, functional languages are not a silver bullet. For certain tasks, especially those requiring complex side effects or where performance is critical, it may be more natural or efficient to not use a functional style.

Let’s build a programming language!

So, what kind of language are we going to build?

We will build a functional-style language (though we won’t make it 100% functional) and compiler that doesn’t use GC (meaning the compiler or user manages memory). However, we will implement ownership control (just like Rust!) so programmers don’t need to manually manage data lifetimes. Why are we doing this? It’s easier to focus on the compiler itself (we don’t have to build interpreters or garbage collectors!), and there are already many good articles about implementing interpreters, so here we want to focus more on compilers.

Why a functional language?

Functional languages are harder to learn for most people, and it’s a type of language that many programmers aren’t familiar with. So why build a functional language? First, from a language designer’s perspective, they’re easier and clearer to define. Second, because most programmers aren’t familiar with functional programming, I wanted to introduce it to you. We will see how it behaves differently from regular programming languages, and what advantages and disadvantages it has. However, even if you don’t build a functional language, the concepts explained here will be helpful.

Hoya Language.

Our language is called “Hoya”. The rest of this article will focus on implementing Hoya. But before we start typing away at the keyboard, let’s first take a look at what Hoya looks like, shall we? Let’s define what we’re building before we start.

Hello world!

Let’s make Hoya print “Hello world!”. Here is the simplest example of the Hoya language.

func main(){

print("Hello world!")

0

}

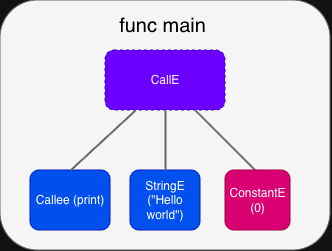

This program can be represented in a simple tree format.

This is what our program looks like (where the suffix “E” stands for “Expression”).

The CallE (call expression) consists of three children. The first one represents the callee (the function being called). The second one is the argument, “Hello world”, which represents a string. The last one is NextE, which represents the next expression to execute. In our case, the next expression is the constant zero.

By representing a program in a tree-like format, compilers or interpreters can traverse it and compile or execute it. This kind of tree is called an AST (short for Abstract Syntax Tree). Converting a program—which is just a string from the computer’s perspective—into an AST is typically the first process a compiler performs. Once the program is converted into an AST, the compiler can start translating it into machine code, or the interpreter can execute it directly.

From the next chapter onwards, we will start designing all parts of Hoya. Let’s explore how a language can be defined and how we define its behavior as each expression is evaluated.